Questions? Call Us 1–773–271–0318 9am to 2pm Central Time Mon.–Fri.

Inquiry–based Learning Lesson

for Immediately Prior to the Introduction of the Standard Flat Periodic Table LessonA Creative Periodic Table Teaching Lesson Plan:

Taming the Dreaded Periodic Table, or

Converting an Element Table into Three Dimensions – not just for Fun

Premise:

Inquiry–based lesson plans are often referred to as "facilitation plans," to help teachers remember their role as facilitator of learning, rather than fount of all wisdom. The notion also helps teachers structure lessons more loosely to allow student answers to questions to drive the learning process without derailing it.

Inquiry is important in the generation and transmission of knowledge. It is also an essential for education, because the fund of knowledge is constantly increasing. Trying to transmit "what we know," even if it were possible, is counterproductive in the long run. This lesson changes the focus on "what we know" to an emphasis on "how we come to know."An old adage states: "Tell me and I forget, show me and I remember, involve me and I understand."When students are first introduced to a new subject, certainly one as critical to Chemistry as the Periodic Table, they require a context, motivation, and foundation from which to understand this new information. First as a preface to learning chemistry, then a constant learning tool for the student, and finally a daily reference for the professional, the periodic table has no peer in science. Early in entry chemistry courses, therefore, is the introduction of the Periodic Law and the Periodic Table – based on the work of Mendeleev and others.

The last part of this statement is the essence of inquiry–based learning.

Involvement in learning implies possessing skills and attitudes that permit you to seek resolutions to questions and issues while you construct new knowledge.

Unfortunately, our traditional educational system has worked in a way that discourages the natural process of inquiry. Students become less prone to ask questions as they move through the grade levels. In traditional schools, students learn not to ask too many questions, instead to listen and repeat the expected answers. The daunting prospect of this methodology for "Learning the Periodic Table" has led it to become an icon of hardship for students, and, indeed, in the common knowledge of the general public.

Preceded by lessons introducing science and scientific method, chemical terms, measurements, matter, atoms, subatomic particles, and elements, the periodic table is instrumental in learning about the properties of elements and how they relate and combine, in short, all of chemistry. Previously, the standard flat periodic table has been the tool employed for this effort.

The flawed image of that popularly accepted arrangement of chemical elements (propagated by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry, the accepted authority) is both confusing and disjointed, and when one begins to associate it with the Periodic Law, the table is also simply wrong in its many departures from the Law, providing an unstable basis for future learning, and introducing (reinforcing?) doubt in authority.

Memorizing facts and information is not the most important skill in today's world. Facts change, and information is readily available –– what's needed is an understanding of how to get and make sense of the mass of data. Effective inquiry needs to be applied to learning in this precursor lesson to the huge, efficient, vital resource for practically all aspects of chemistry, that is the flat (of necessity) Period Table, involving several factors: a context for questions, a framework for questions, a focus for questions, and different levels of questions. Inquiry learning produces knowledge formation that can be immediately applied to the following lesson.

By completing an enquiry–based lesson involving the students in modeling the periodic table – literally – by themselves, and creating an example of a periodic table with all of the tabular data and relationships intact, will interest, inform, familiarize, produces knowledge formation, and generally ease every student into the next lesson – on how to appreciate and use the flat periodic tables. (Can fun and periodic table be in the same lesson...The same sentence?)

The desired outcome, pictured in photos of the completed 3D construction, is reached by conversion of parts (rectangular shapes containing element boxes) of a periodic table printed in color on card stock to be cut out and manipulated for learning purposes by answering and applying those answers before, during, and after their assembly into a three–dimensional periodic table.

1. What do these shapes make you think of?Student interest, motivation, and curiosity, is enhanced by joining with classmates in interactive activity, that of building a dimensional and colorful device which requires identification and physical manipulation of element groupings and learning/applying these interrelationships.

2. In what ways are the shapes the same?

3. In what ways are the shapes different?

4. If you put them in size order, of what does that remind you?

5. What do the small boxes represent?

6. What do the numbers mean?

7. Are some shapes larger/smaller than another?

8. Is there anything else you could do with the shapes?

9. Are there names for the shapes?

10. What are some different things you could try?

11. How do the numbers line up?

12. Do all the numbers line up when you put the blocks together?

13. How are you going to fix that?

14. What did you do?

15. How do the numbers line up now?

16. What will you do next after you finish that?

17. How do you know when you are finished?

Student achievement is facilitated by the procedures necessary in the construction of the model, providing a series of motivational successes. Easing understanding by breaking the task down into "doable" steps that can both incorporate prior knowledge (but not require it) presents complex concepts rationally and correctly, framing the upcoming lesson material into a familiar context. Learning is tiered by this step–by–step approach, in that every part has its own story, and reasons made clear for why they must ultimately end up attached to certain others.

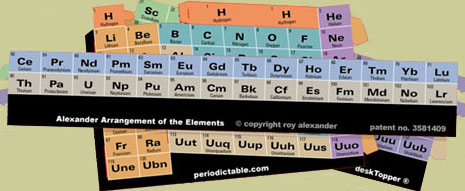

Providing students with an opportunity for physical and intellectual participation in the examination and creation an example of the desired outcome, a teaching and learning opportunity not afforded by viewing a flat table. This may particularly apply to the less academically oriented students. Gender differences may also be positively addressed, relating to the following statement from the Gurian Institute; "In combining brain research with wisdom–of–practice research in schools, we have learned that the way we support boys' learning styles can improve student performance... One successful way to support the male brain is to use "graphic brainstorming." This innovation brings a whole brain approach to [learning]." Assembling a model of the Alexander Arrangement of Elements is "graphic brainstorming" on steroids!

As instruction continues in subsequent lessons, the Alexander Arrangement should be gradually withdrawn so that students will eventually be able to independently demonstrate comprehension of other representations of element relationships.

The model can be folded for storage or brought home as a souvenir of one's first introduction to the Periodic Table – possibly for continued handy reference.

Teaching Ideas for Using the Alexander Arrangement of Elements in Class